The timing of life’s peaks and valleys are unique depending on the individual in Black America, but the experiences themselves are synonymous. We all deal with the task of navigating through terrain specifically designed for us, yet not designed in our favor. The socioeconomic makeup of the cities we come from teaches us to be communal and operate in self-interest at the same time.

The dynamic of our relationships includes a protective instinct as we care for each other in nuanced ways while playing tug of war over a certain type of respect from our significant others. We treat our close friends like siblings while keeping each other at a metaphorical arm’s length for fear of exposing our weaknesses, thereby giving too much power to anyone.

Stepping into our individuality is a fight in and of itself as we reluctantly turn away from the mindsets and habits molded by our predecessors, in favor of new ideologies that fit our perspectives of the world we eventually encounter on our own accord. There’s a powerful duality that we inherit with our brown skin, and John Singleton was a master of explaining it through is directorial lens.

THE DUALITY OF BLACK MEN

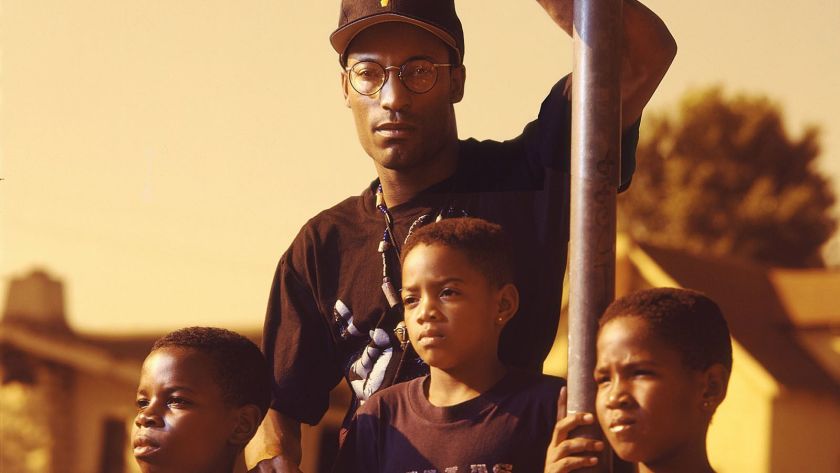

At 24, John Singleton put Hollywood on notice and South Central LA on display with Boyz n the Hood—a masterpiece that showcased the spectrum of young Black men versus the generalization of us, pumped through the propaganda machine known as American news. In the film, a gifted young boy named Tre hits the time limit on the safety of his mother’s nurturing embrace, and is transitioned into lessons on manhood through the guidance of his father.

It’s a distinct adventure each Black man has to face. Those of us who were unfortunately raised without fathers received our lessons in manhood from the uncles, cousins, coaches, and various other “father figures” within arms reach. Regardless of the teacher, the lesson remains the same. The world doesn’t love you like your mother does, and it never will. When you jump off the porch and into society, you’re public enemy number one, and you’d better learn to be productive despite the burden. You’d better grasp that being a Black man is a job and it’s on you to find a way to carry its responsibilities, even if you get so frustrated that you end up punching the air.

For every Tre there’s a Doughboy, a kind heart hardened by his surroundings. The good in him occupies an equal amount of bad. The good is what he wishes consumed him, and the bad is what he depends on for survival. How can you judge him for being balanced? Is it because he doesn’t look inviting? Is it because his charm comes with a hint of mystery? You can’t quite tell what he’ll do if you bring him the wrong energy, can you? Good, we make you feel like you should be on your toes around us because we live like that everyday.

Those are instincts we need so we don’t end up like Ricky: robbed of our potential because we got caught slipping. The robbery of our potential doesn’t always end in gunfire. Sometimes it ends in losing that scholarship, or that promotion we had a shot at. If we’re not on point at all times, we’ll end up taking two steps back from the forward step we just took. Worst case scenario, we end up dead, never taking a forward step again.

EXCHANGE OF POWER AS LOVE LANGUAGE

Just two years after releasing Boyz n the Hood, John Singleton gave us Poetic Justice, this time painting a picture of the complex relationship between young Black men and women. The film’s main character Justice lost her boyfriend unexpectedly to violence, leaving her skeptical of opening up again. Lucky, her love interest played by the late Tupac Shakur, had good morals, but didn’t understand how to engage a woman that required more than sweet talking and humorous wit.

I can’t speak for women, but as a man I know what it’s like to give love and decide I didn’t want to anymore. Most men are guilty of that. Until a certain age, we don’t think much about how deeply some of our gestures resonate, and how traumatic it must be to impact someone emotionally, to just move on without thinking twice. I’m not sure if we do that because we’re afraid of being vulnerable, or because we’re as emotionally unintelligent as people say. Maybe it’s both, but either way, we’re a bit entitled with how we handle love.

As we grow older, we encounter women who have developed a force field around their hearts, weary of repeating the same let downs that come from our fear of vulnerability. That’s where we butt heads. As men, we may have good intentions with the women we forge relationships with, but good intentions aren’t enough. It’s about consistent action, and creating a safe space for a woman to let her guard down.

“I’M A BLACK WOMAN, AND I DESERVE RESPECT.” – JUSTICE, POETIC JUSTICE

Lucky and Justice challenged each other in that sense. On one hand, it’s perfectly natural to be protective of your feelings. It’s equally as natural to expect to be taken as you are, even if there’s potential to be better. Black men and women are everything to each other, even when we’re too stubborn to see it. We go through exchanges of power, until deciding to meet in the middle and understand the reasoning behind each other’s flaws.

We saw the experience played out just as much in Baby Boy. The story of Jody, a 20-something Black man struggling to take ownership of his transition out of boyhood. He has two children by two different women, one of which he loves, and both of which he expects access to when he feels like it. Yvette, the woman who has his heart, displays the type of patience he doesn’t deserve. She provides for herself, maintains a roof over their son’s head, and still welcomes him with open arms although his presence is inconsistent. He’s quick to name the small things he does for her: buying groceries here and there, installing cable, and putting rims on her car—small gestures that to him say “I’m making sure you’re comfortable”, but they pale in comparison to what Yvette really wants.

She wants to know they’re a family, that she can depend on him. Her frustration manifests in locking him out of the apartment. He hits back by refusing to fix her car. Small incidents, both of which are attempts to gain some sort of leverage. In the end they come together the minute Jody realizes that he can’t fight his woman until she bends to his will. He’s got to give as much as he’s hoping to receive, maybe even a little more. That’s the essence of being a provider.

“IF I’M INSECURE IT’S BECAUSE YOU MADE ME THIS WAY, ALL YOU DO IS THINK ABOUT YOURSELF.” – YVETTE, BABY BOY

The Black woman demands that we realize the power in our potential. She knows that her love for us doesn’t require her to settle for half of us. She welcomes being led, as long as we’ve actually got a direction in mind. The irony in that is it takes time to find direction, and maybe we’d like her to know that not having direction yet doesn’t mean we’re not in search of it.

OPTIMISM VERSUS REALISM

In Higher Learning, Remy and Malik show the juxtaposition of the mindstate most young Black men deal with at educational institutions. Malik is there on scholarship, while Remy is a senior on his way out. Remy is militant, and almost exhausted at the racism he sees daily. Malik is hopeful, a wide-eyed freshman aware that the institution he’s operating within has its own cultural barriers he’s got to work around.

In a back and forth with his Black professor, Malik seems to expect a break because they share the same skin color. That is a distinct experience we have as Black people, so artfully showcased by Singleton through character dialogue. At times, we mistake support for a free pass. Racism is a great hindrance to our progress in this country, it’s an indisputable fact. Be that as it may, we still get in our own way at times by believing that when we see each other in spaces where there are few of us, that we shouldn’t hold each other to high standards. We sell each other short looking for the hook-up when it’s more productive to help each other earn what’s for the taking.

“I WILL CONTINUE TO GIVE YOU A DIFFICULT TIME, UNTIL YOU HAVE PROVEN THAT YOU DESERVE OTHERWISE. THOSE ARE THE RULES OF THE GAME. YOUNG MAN YOU HAVE TO RID YOURSELF OF THE ATTITUDE THAT THE WORLD OWES YOU SOMETHING. YOU MUST STRIP YOURSELF OF THAT ATTITUDE, IT BREEDS LAZINESS.” PROFESSOR PHIPPS, HIGHER LEARNING

Meanwhile, Remy appears almost jaded at having a higher education, because the struggle doesn’t change. What good is a degree, certificate, or any other credential if at the end of the day, it’s our skin that determines how our trajectory? He’s not entirely wrong to carry these thoughts, but it’s dangerous to accept that reality. If we keep a bleak outlook on our potential then we’ll never move forward.

We must embrace hope just as we embrace the survival mentality. Both are necessary, but neither is beneficial in excess. There are countless other movies and an iconic music video I can choose from and dissect, but the message is clear: John Singleton knew the value in helping us see ourselves, never shying from the stereotypes others may have run from.

Instead, he revealed the beauty in our madness, and the genius in our ignorance. Black people aren’t perfect, nor do we come perfectly packaged. It’s our various dimensions that make us a galaxy worth learning and understanding, for the benefit of our own higher learning.

*Original article by Dev T. Smith via Cassius.com

Recent Comments